Images#

One of the applications of computers is representing image data. We will discuss what an image is, analyzing images, and manipulating them.

Grayscale Images#

To start, let’s consider black-white images, which are commonly called grayscale images. Here is a picture of a grayscale dog.

From the computer’s perspective, we think of images as just a big grid of values called pixels . This mirrors how your screen actually displays images! It is a bunch of these pixels that can show a color based on a specified value. For a grayscale image, each pixel needs to know how white or how black it should display.

Conventionally, we represent each pixel as a number between 0 and 255. 0 is the darkest value possible (black) while 255 is the lightest value possible (white). This means a grayscale image is really just a big 2D array of numbers between 0 and 255!

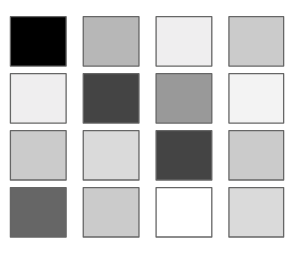

You could imagine a low-resolution image (one with very few pixels) would look something like this

In Java , we would represent this with a 2D array with values that look something like the following.

{{0, 100, 175, 120},

{180, 61, 83, 130},

{118, 137, 59, 121},

{73, 133, 237, 140}}

Where the values are low, we get darker colors, while where the values are high, we get lighter ones. The dog image above is just a really large 2D array of these values 0 to 255!

Note

At first glance, 255 might seem like an arbitrary number. So where does it come from? It turns out that 255 is the biggest integer that can be stored in a single byte of information. For grayscale images, we typically use one byte to store each pixel in the image. That means saving a grayscale image with ~1000 pixels would take up ~1 kilobyte (i.e. ~1000 bytes) of memory on your computer.

Color Images#

We are going to use a data structure called BufferedImage to help read in an image to an array. A Grayscale Image stores all the values in a 2D array while Color Images use a 3D array.

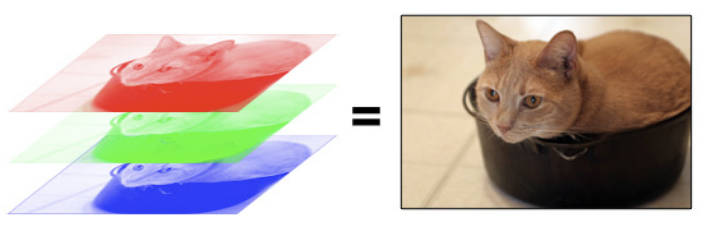

Let’s brighten up the world a bit and switch to color images. A color image is commonly represented in a format called RGB. RGB stands for “Red, Blue, Green”. An RGB image is really just 3 “grayscale” images stacked on top of each other, but each sub-image corresponds to a particular color channel.

So each pixel in an image is really 3 numbers to tell it how much red, blue, and green respectively to output. Your brain does all the real work of combining how much red/blue/green corresponds to a more complex color like the orange/brown color that the cat is.

In turn, an array will just have to represent all 3 colors for each pixel. Each pixel will store 3 values between 0 and 255; a low value means that color channel is more off (black) while a high value means that color channel is more on (red, blue, or green respectively). Since each pixel needs to know 3 numbers, we will represent this as a 3D array.

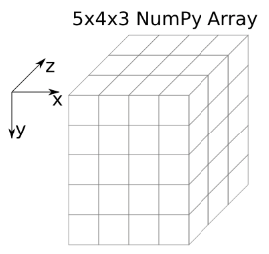

A color image in Java will commonly be represented as a BufferedImage. However, it doesn’t take much code to transform the information into 3D array with dimensions [height][ width][3] . The last dimension has size 3 because there will be one dimension for each color channel at that pixel location. Visually this makes it kind of like a cube that has “depth” 3 (in the z direction).

To index into a color image, you now need to specify 3 values. For example, img[row][col[channel].

Convolutions#

There are some very simple ways of transforming images by simply changing all the RED values to 0. We will now describe a very useful type of operation done in image analysis to help extract local information in an image. An example of local information would be something like “is there an edge in this part of the image?” This type of approach for analyzing images has been instrumental in building state-of-the-art image recognition systems used today (more on this later). The type of operation we are going to describe here is called a convolution.

The idea of a convolution follows from it being a sliding window algorithm: an algorithm that moves through the data looking at a certain-sized region of the data at a time. A convolution is a special type of sliding window algorithm that we run over an image. In a convolution, we use another 2D array, called a kernel, that we use to compute a value for each location. The result of a convolution is a smaller “image” that stores the result of the computation for each sub-region. This is much easier to understand visually with an example.

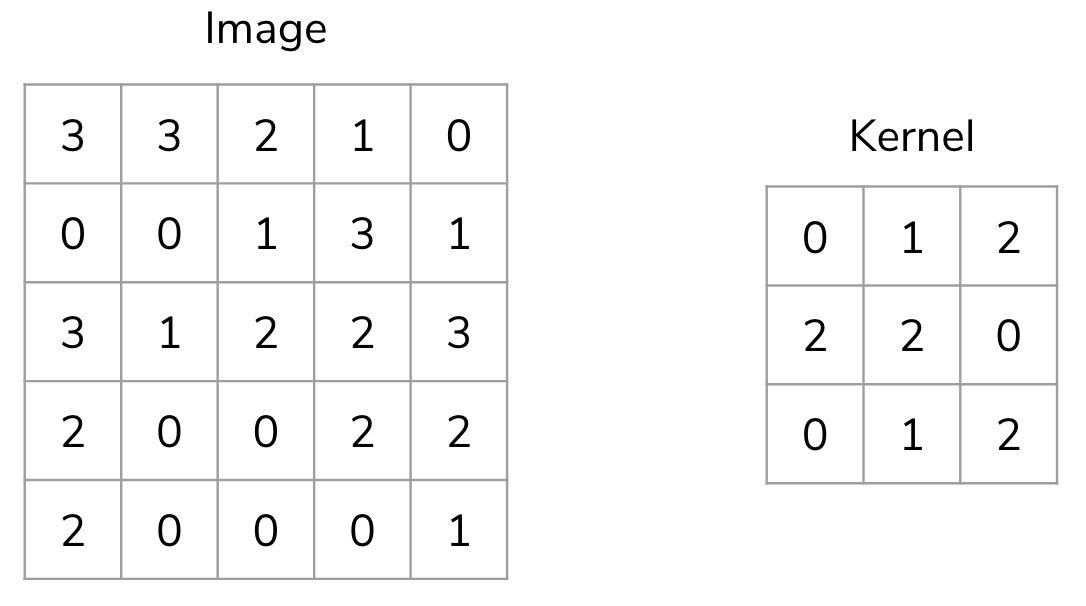

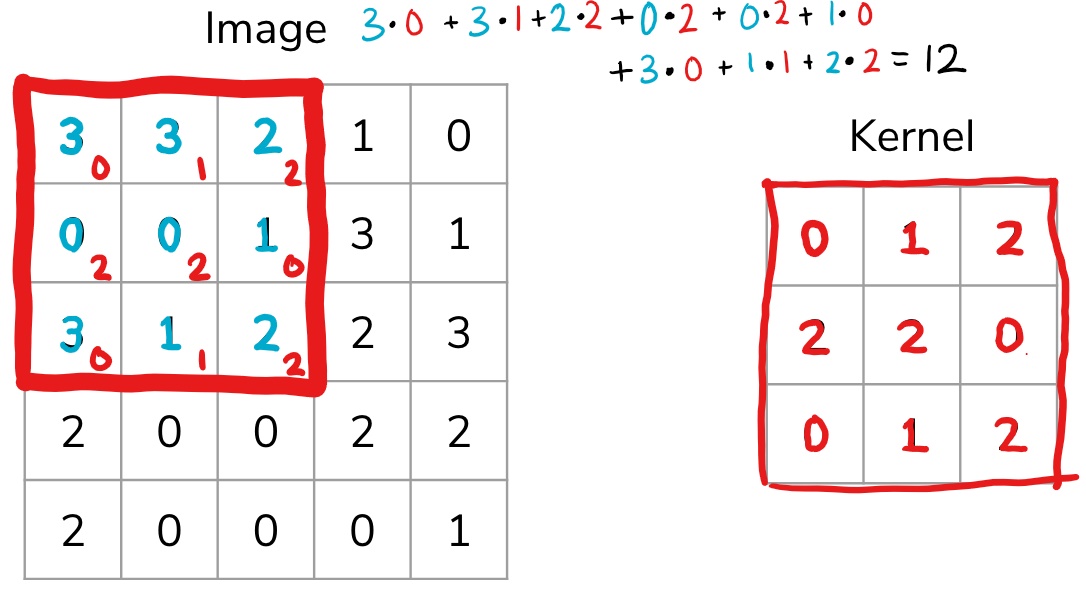

Suppose I had the following input image [5, 5] and a smaller 2D array that we will use as the kernel [3, 3].

We start by overlapping the kernel at the top-left of the image shown in the image below. We compute an element-wise product between the kernel and the part of the image it overlaps with and then compute the sum of those values to be the result for this location. So the image below shows the sum of the element-wise product being 12 for that position of the kernel over the image. We then move the kernel to the right one position and repeat this process. Once, it reaches the right side, it goes back to the left but starts one row lower until it’s hit every possible part of the image.

This whole process is best seen in an animated fashion to show all locations the kernel visits. In the GIF below, the blue image is the original image, the darker blue area is where the kernel currently is (and its values are shown in the bottom right of each cell), and the resulting image is shown in green.

Notice how this convolution computes a value for each part of the image. This is what we mean by “local information”. The kernel (which you choose) computes some value for each part of the image, and the result can then be used to do some analysis based on those values.

You are probably thinking that these kernel numbers don’t make a lot of sense and this process doesn’t seem that useful, which is fair. However, you can do some pretty clever things using this approach depending on which kernel you use!

Types of Kernels#

There is a bit of an art to deciding how big (i.e. its shape) the kernel should be or what numbers you should use inside of it. For a while in the late ’90s and early ’00s, computer vision experts spent a lot of time hand picking numbers that seemed to work in practice with okay performance. Nowadays we use machine learning to learn the kernel values for us!

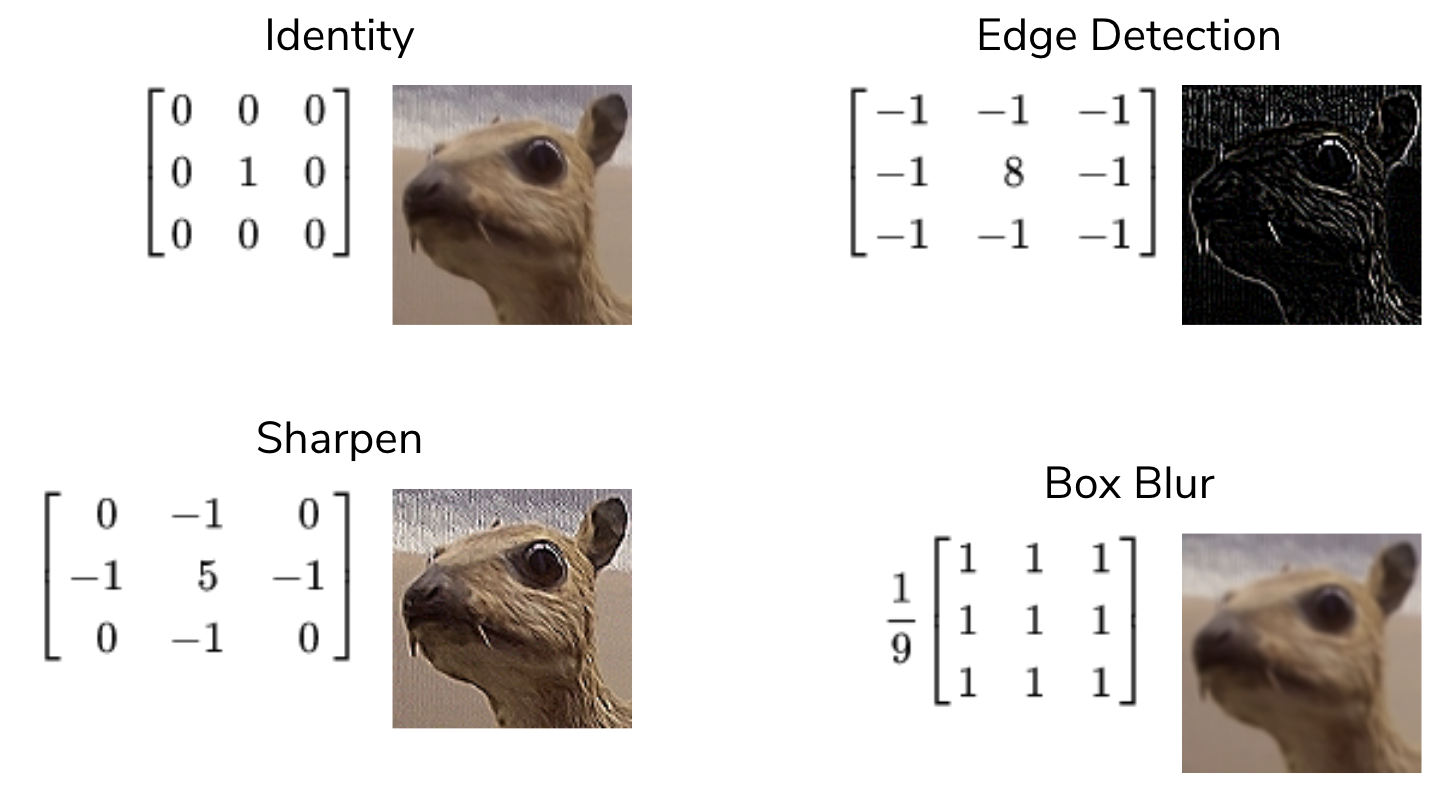

The image below has some example kernels that are used in practice and what they are used for. We won’t explain all of them because the numbers themselves aren’t important. The cool thing is that all of the operations they implement (edge detection, sharpen, box blur) are all different from our perspective, but are actually just the same convolution operation with different kernels!

To get an intuition for why these do what they do, consider the edge detection kernel. It has the value 8 in the middle and -1s all around it. This kernel helps detect edges. What this means is that in the resulting image, places with high values (showing up as white in the image above) correspond to edges in the original picture.

Why does this kernel accomplish this? Consider an image that was all the same shade of blue for all pixels in the image. This image would clearly not have any edges in it since all pixels are the same color! If we think of a convolution using this kernel, at every location, the kernel overlaps with the image, the result will be 0! You can convince yourself of this since any pixel value in the center will add 8 of itself to the result, but then its 8 surrounding pixels would contribute -1 of themselves to the result. Conversely, the result using this kernel is non-zero when there is a large difference in the color at the center and those around it. This is exactly why this kernel detects edges!

This content originated from Hunter Schafer at UW. See original content here and here.